I’ll be honest…when I first started working in the schools as a speech language pathologist (SLP), I wouldn’t have been able to tell you what speech sounds (how you say/pronounce sounds) had to do with reading. I probably would’ve said nothing, and I would have been SO WRONG.

Kids with speech sound difficulties, like not being able to say their Ls or Rs, are at much greater risk of having difficulty with reading down the road if they aren’t given the right kind of support.

So what’s the connection?

In the simplest of terms, there’s this relationship–first, you have oral language–what you can say. You can say sounds, or you learn how to say sounds. This is where kids sometimes start with speech challenges. When your kiddo is saying “woad” instead of “road,” he might have trouble with saying an “R” sound.

After kids can say all of their sounds (think preschool age-ish) we expect kids to be able to use those sounds they can already say and start to play around with them. We read them rhyming books, sing nursery rhymes, and might start to point out the beginning sounds. Think about our friend who can’t say his “R” sound again. Maybe his name is “Ryan,” but when we point out “Hey, your name starts with “rrrrr,” he might be confused…because when he says it, it sounds like “Wyan.” Can you see where some of this already starts to break down?

Eventually, this playing around with sounds becomes putting sounds together or taking them apart, and connecting them with letters. By early elementary, kids are asked to combine a couple of sounds to make words. A teacher might say something like “Let’s blend these sounds together…rrrrr…..aaaaaa……tttttt…What word does that make?” Her students should answer “Rat,” right?

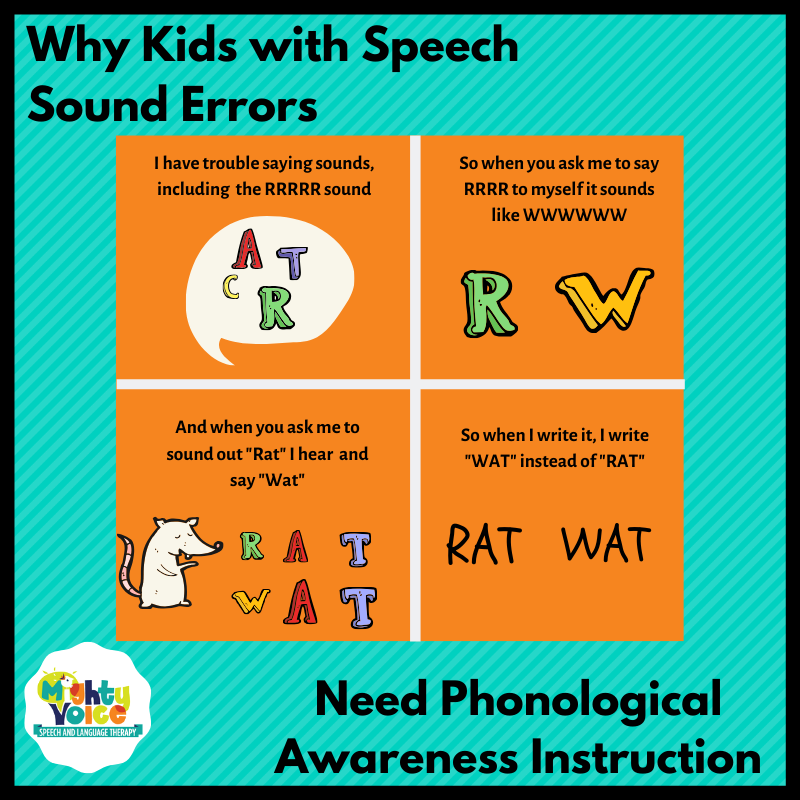

But think again about Ryan. Maybe he’s sounding them out to himself, and if he hasn’t had any help with that “R” sound, he goes “wwww…..aaaaa…..ttttt” and doesn’t come up with “rat,” but instead “wat.”

Eventually, we’re going to ask kids to connect their knowledge about sounds with the alphabet. We’re going to teach them that there’s a written letter that goes with every sound they know. For most kids, it’s already a task to remember that this shape they see, the “R” their teacher wrote, goes with the “rrrrrrr” sound.

Again, there’s Ryan. When he’s trying to remember which shape on the paper goes with which sound, maybe he says that sound to himself, and if he hasn’t had therapy yet, he still says “wwwwww” and now he’s confused…does that sound go with the “R” that’s written there, or the “W”?

Eventually we ask kids to use this knowledge of which shape goes with what sound to write. So for most kids, we say “Okay, write the word ‘ring'” and they know that the shape for the letter “R” goes with the sound “rrrrr.” So they sound it out for themselves and write it down.

But, if you still haven’t had any help with saying that sound, and you sound out the word “ring” to yourself, it might sound like this “Wwww…iiiii….nnngg” and so you write “wing,” and then when you get to your spelling test it’s marked wrong.

You’re starting to see how this all falls apart for Ryan, right? So what he needs instead is a couple of things. First, he probably needs some help being able to produce that “R” sound. For that he needs a speech language pathologist.

Then, once he say produce that “R” sound, he may also neednsome extra support to help reinforce those connections–being able to produce the “R” sound, make rhymes with it, hear it at the beginning, middle or ends of words, connect it with the written shape that is the letter “R.”

He needs someone to help him with phonological awareness–all of those tasks that connect oral language, how he says his sounds, with how sounds connect with each other, and how sounds form words and letters, and words form sentences.

Which is why I would argue that any time we’re treating students with speech sound disorders, we should also be targeting their phonological awareness skills. We don’t know which ones will go on to have solid literacy skills, and which ones are going to struggle. They need us to help make sure their foundations are secure, so that those connections that eventually lead to literacy don’t crumble.

So how do we do that? I’ve written another post addressing some of the “how,” which is a great place to start. If you’re an SLP, and not confident in your knowledge, find a great reading teacher friend and ask questions. Seek out professional development related to early literacy skills. I think you’ll be amazed at the connections and overlap when you break it all down.