Years ago, long before I had children, an interest in auditory verbal therapy, or a degree in speech language pathology, I remember being incredibly impressed with a friend’s toddler’s vocabulary. She was repeating names of fish on a poster. Names like “pickerel,” “lake sturgeon,” and “common carp” rolled off her tongue. I kept telling the friend how smart her kid was, but she wasn’t as impressed. She explained that when all of the words your child is learning are new, one word is not really any more difficult than another. Which made sense…if you don’t know either of them, and they’re equally easy to say, like “fish” or “bass,” you should be able to pick up either one.

Here are some other things to consider when you’re thinking about teaching your hearing or deaf/hard of hearing child new vocabulary.

Knowing a word isn’t just knowing the dictionary meaning

There is SO much more. Think about the word “car.” You probably know the dictionary definition. It’s a vehicle with 4 wheels, but that’s not everything there is to know about a car.

We took a trip this past week with our two children and my husband to visit my husband’s family on the East Coast. When we arrived at the airport car rental center, our toddler had tons of questions about our rental car. He wanted to know whose car it was, so we talked about the more specific term “rental car” and explained it meant we paid some money to use a car for a while and would then bring it back. He also wanted to know “What kind of car is it?” so we talked about that it was a Subaru Outback and how that was the name of the car we were using. Then he started talking about what was the same about the rental car and our car–they were both black. I jumped in and pointed out some differences to him–this was a car and the car we have at home is a kind of car called a van. Just in this exchange we had discussed a new vocabulary term (rental car), names and brands of cars (Subaru outback), similarities and differences, and categories (van vs car vs truck).

Motivation and context are everything

It’s fair to say our toddler has probably never even seen a radish, much less eat one or know its name. Honestly, my husband and I almost never eat radishes. We got some in a CSA a few years back, and after cooking them decided they tasted like a combination of dirt and feet.

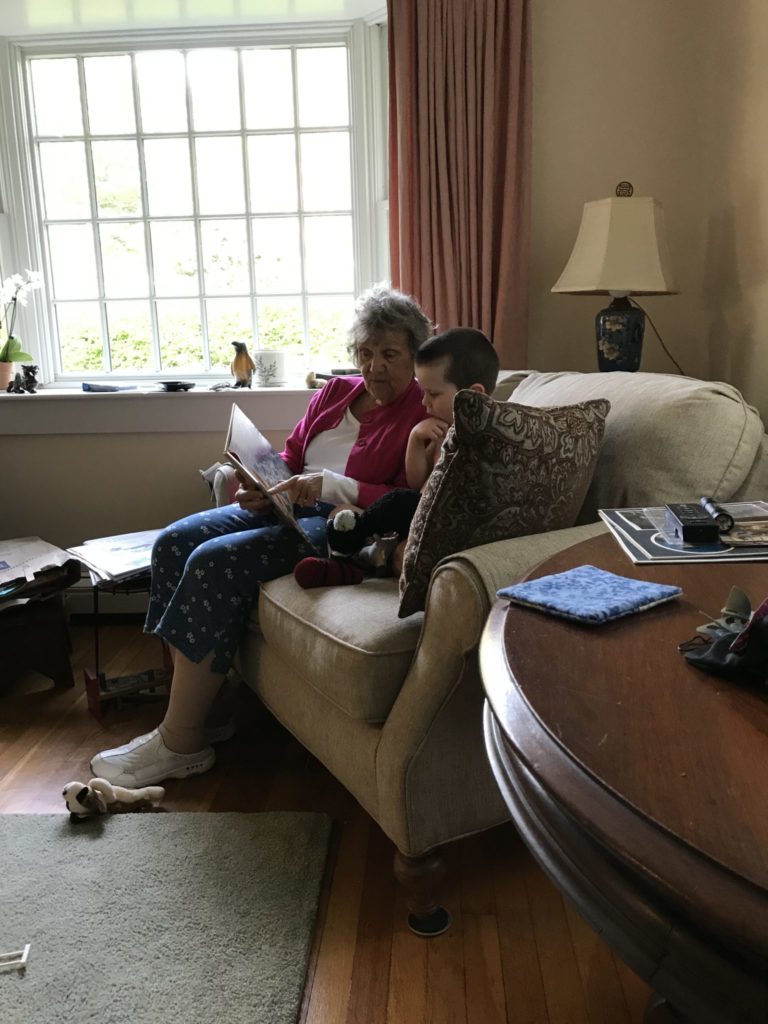

But, this past week on our trip, when he discovered he could dig them out of his YiaYia and Grump’s garden, he learned the word “radish.” He pulled one out of the ground on the first day, and with his YiaYia cut it up and walked around the house handing each one of us a piece (don’t tell him mine went straight into the compost).

A few days later, he asked if he could go and dig up “dishes.” It took us a while to figure out he was asking for “radishes.” He again dug one up, watched YiaYia cut it up, and decided who could have a piece (or not) in typical toddler fashion. By the time he was done on the second day, he could say “radish,” and when we later looked at pictures of him holding it, he said the word “radish” himself.

I think I could have taken him to the grocery store and pointed at a radish and named it and he wouldn’t have had the least interest. We probably could’ve done this multiple times with the same result. But, since it was interesting and motivating to him, and involved some of the people he loves the most, he learned and used the word.

For children who are deaf and hard of hearing, it may take more repetitions or explanation, but when you find something they’re interested in or curious about, take that opportunity and run with it. We all know kids who can talk at length about their favorite type of dinosaur or minecraft character or doll. It’s all about interest and motivation.

Kids need kid friendly definitions

When thinking about teaching our kids anything new, I think Elizabeth Rosenzweig’s “Just One Hurdle” principle is important. Her explanation is great and worth a read, and can be summarized like this–when you’re teaching a child something new, keep it to just one new thing at a time. So when we’re teaching our kiddos a new word, we want to keep our explanations of that new word simple by using words they already know to explain it.

We had so many opportunities to practice this on our trip, and even as an SLP I need to practice…defining words isn’t always easy! Don’t worry if it doesn’t come naturally to you, you’ll get better as you do it.

As we flew home, my son wanted to know “What is this called?” on the jetway. I told him something like “This is a jetway…it’s a big hallway we walk through to get from the airport to the airplane.” We struggled to come up with a kid friendly definition of a lighthouse, and settled on “It’s a big flashlight that you can walk inside that tells boats where to go.”

Repeat, repeat, repeat

Research varies, but it suggests that children with typical hearing need to hear a new vocabulary word somewhere between 12-40 times in order to understand and use it. If you consider that children who are deaf and hard of hearing may be missing some of those exposures due to background noise, fatigue, or other factors, we need to offer even more repetitions.

The word repetition may make it sound boring, but it doesn’t have to be. In the radish example, my son’s grandparents repeated the word many times while helping him dig it out of the ground. When he offered it to the adults, he heard it again as we asked “Oh, what are you giving me?” and then again when he wanted to dig them up a second day. If we wanted to continue repeating it with him, we could think about incorporating radishes into our meals (unlikely) or checking out a book about vegetables or watching a Youtube video with radishes (much more likely).

Help your child make connections

Another way to increase repetitions, and to link vocabulary with literacy is to make connections, which is just a fancy way to say explain to your child how the word is related to something else in his or her life. The more you do this, the more your child will start to make connections on their own.

After seeing the lighthouse and explaining it like a big flashlight, my son’s grandmother brought home a book about lighthouses and the littlest lighthouse keeper. He was enthralled. A few days later in the grocery he told me he saw a lighthouse. I was skeptical, but sure enough, he had spotted a display for Cape Cod Potato Chips like this one, which features a lighthouse on the logo.

Parents of children who are deaf and hard of hearing, particularly those who are seeking listening and spoken language outcomes, are already experts at narrating their day for their children. Don’t think of vocabulary instruction as another item on your to-do list. Instead, I hope some of these tips make it easier for you to incorporate more vocabulary knowledge into what you’re already doing. And remember, you are your child’s first and best teacher, and you’re doing a great job.